Leaders, the paradoxes of onboarding

Patrick is a 49-year-old executive who has always been successful in his career. After a long selection process, he is chosen to lead a business in the health sector. This company has a strong identity based on a sense of patient service, “esprit de corps“ and the employees’ great pride in the history, values and mission of the organization.

Patrick’s predecessor was not really a charismatic leader. He exercised leadership based on the search for consensus in his decision-making. Patrick took office without a real transition period with his predecessor, which did not seem to be a concern for him.

During the first months of his tenure, Patrick multiplied contacts with employees to share his vision and enthusiasm. Unaccustomed to this type of approach, the majority of employees fell under the spell of this charismatic leader capable of transmitting his energy and his ambitious vision of a motivating future. Thus, in a very short time, Patrick seduced all his interlocutors: his board of directors, the members of his management committee, the employees and most external stakeholders.

Despite this, after a little over a year of employment, the board of directors decided to let Patrick go.

Onboarding: a period littered with contradictory expectations

The period of onboarding is where the executive will rapidly create his leadership image. This first impression conditions his credibility and his ability to mobilize his organization. Once established, this social image will take time to be erased and transformed.

Patrick, despite his qualities, did not succeed in meeting the expressed or implied expectations of his role. These often contradictory and sometimes paradoxical expectations would have required Patrick’s to adopt positioning, behaviors and actions that might seem to be opposite.

We have grouped these contradictory expectations into six paradoxes to which a new leader must pay great attention in order to succeed in onboarding.

- The first paradox concerns the need for a leader to support and demonstrate a certain self-confidence but also to be able to convey an image of During the first weeks, he finds himself observed by all. His gestures, his words, his posture, his decisions are scrutinized by all stakeholders. He becomes the new incarnation of the function he discovers. Thus, he must, on the one hand, reassure everyone about the choice made by the organization to choose him and thus reassure stakeholders on his skills and abilities to fulfill his role in the particular context of the organization. On the other hand, he must be able to listen, to learn, to take the time to reflect and to take a step back to decoding and understanding the new complex environment in which he must evolve. In a certain way, an executive is expected to quickly embody his function by affirming his convictions and sometimes even his certainties by sharing an engaging and dream-inspiring vision, but at the same time take the time to feed on his new environment so that the transplant can take hold.

- When onboarding, a leader must also quickly demonstrate his ability to be operational and bring tangible results in the short term. His ability to be active and to adjust his pace to that of the organization he joins is proof of his ability to generate value and a way to legitimize his “raison d’être”. This focus on action, which is often natural for a leader who has built a career through personal investment and a strong desire for accomplishment (McClelland, 1984), must be balanced with a need to rise above the hubbub and hustle and bustle surrounding his taking office. Demonstrating strategic thinking (Liedtka, 1998) and taking the time to think of the organization as a system are essential for succeeding in onboarding. However, two extremes to be avoided are taking too much action by focusing on immediate results or thinking too much and getting lost in uncertain futures.

- Another paradox facing the executive regards leadership and management. Usually, each new leader has been selected for their leadership abilities (guiding, influencing, and inspiring) and managerial skills (planning, organizing, and controlling). In the period of onboarding and under the pressure of the environment or for personal preference, it is not uncommon to see an executive favorize too much one of these two roles. It is necessary then that the leader takes care to split his efforts, his energy and his actions between his two roles in a balanced way.

- Accepting ambiguity and gray areas are essential for a leader, especially when onboarding. Ideally, he would like to understand everything, to quickly be familiar with everything. But this unrealistic goal would require a full-time investment from the leader. He must therefore accept not to understand everything, to accept the unknown, the approximate and a certain lack of knowledge. At the same time, during the first few months, he must work to clarify what is necessary and essential. To do this, he must dig and remove any ambiguity around the crucial elements in the exercise of his Making the distinction between the acceptance of ambiguity and the need for clarity is often one of the most delicate challenges that the executive will have to face at the beginning of their function.

- Demonstrating your passion, being able to share your enthusiasm and energy are definitely assets to positioning yourself in a new role. Do we not expect a leader to share his desire and make us dream? Nevertheless, we also expect him to be the guarantor of a certain rational objectivity and to demonstrate his ability to be above and beyond his function and organization. In a way, he must be able to position himself at the heart of the organization and teams but also outside the system. To do this, he must detach himself from his fears, his certainties, his ego and he must accept to exercise his power through others (McClelland, 1984). This paradox requires the leader to pay particular attention to his actions, his personal investment and the social image he wants to project.

- Finally, the last paradox concerns the solitude of the leader during the period of This may seem strange as these first months tend to be a time where the leader is the object of everyone’s attention and solicitude. Although, during this initial period, the leader’s diary may be full of meetings, presentations, discussions and interactions with others, this is also a period of real solitude, during which time the leader cannot fully rely on any ‘trusted ally’. Trust (Maister, Green, and Galford, 2002) is under construction and requires that common learning develops with his stakeholders. He is therefore often at the center of a bustling court but without real trusted collaborators with whom he may exchange and share his questions, reflections, discoveries and his fears.

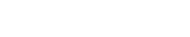

Returning to Patrick’s case, we can schematize how he took on his new role in the following way:

Ainsi, durant les premiers mois de sa prise de fonction, Patrick a su, par son activité, ses actions, et son comportement, démontrer une grande confiance en lui, une capacité à projeter son organisation dans le futur en élaborant et en communiquant une vision ambitieuse. Il a également su partager sa passion et son énergie et accepter son rôle malgré de nombreuses zones de flou.

Malgré cela, la prise de fonction de Patrick est un échec. Pour lui tout d’abord, mais également pour l’organisation, son conseil d’administration, ses employés. S’il est difficile de calculer précisément le coût d’un tel échec, il est facile d’imaginer les coûts réels et cachés d’un tel fiasco (coûts matériels liés au recrutement du dirigeant et à son départ, coûts liés à la désorganisation résultant de sa courte période de direction, coûts humains liés à la perte de motivation et d’engagement des employés, coûts liés à l’impact sur la crédibilité et l’image de l’organisation…)

Probablement, Patrick n’a pas réussi à interpréter les différents rôles qui étaient attendus de lui. Il n’a peut-être pas réussi à naviguer au-delà de ses préférences et ainsi s’adapter aux besoins et à la culture de l’organisation qu’il a rejoint. Dans un prochain article nous reviendrons sur les raisons de cet échec.

Références :

- Liedtka, J. M. (1998). Strategic thinking: Can it be taught? Long Range Planning, 31(1), 120‑129.

- Maister, D. H., Green, C. H., & Galford, R. M. (2002). The trusted advisor. London: Simon & Schuster.

- McClelland, D. C. (1984). Motives, personality, and society: selected papers. New York: Praeger.